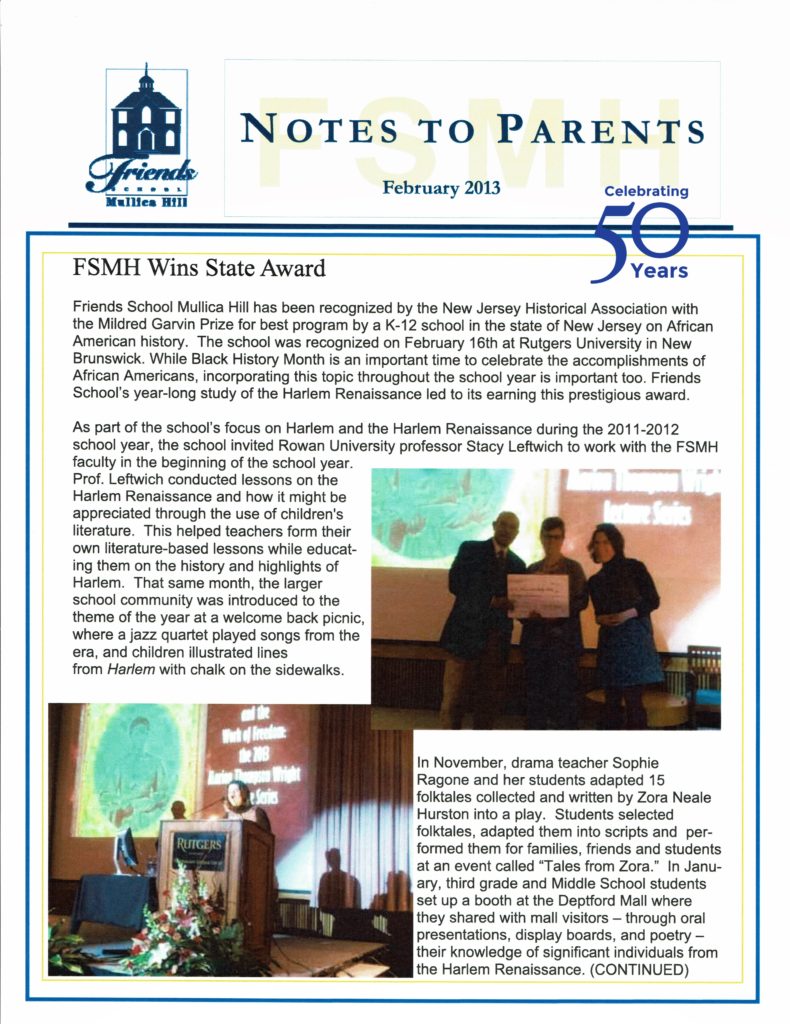

The hiring of the first African American Head of School was an important moment in the history of the School and coincided with an important statewide award given to the School for work done the year before Reaves became Head. On February 16, 2013, the New Jersey Historical Commission awarded the School the Mildred Garvin Prize for the best African American History school program in the state of New Jersey. Teacher Sophie Ragone accepted the Award on behalf of the School in Newark before an audience of a thousand. During the 2011-2012 academic year, staff and the Multicultural Network had selected the “Harlem Renaissance” as the focus for the year’s diversity programming. The School organized an extended celebration of African American history that culminated with a Middle School field trip to Harlem itself. Receiving the award was welcome recognition for a School that had long struggled to live and teach the Quaker testimony on equality. Between 1969 and 2019, race relations remained a persistent and important issue for the nation and the School. From the very beginning at Woodbury, the School was open to children of all races and backgrounds. Yet, the School did not always have many students of color or staff of color. According to Kimberly Camp, an African American who was part of the School’s first graduating class, there were only 5 African Americans in the Upper School when she graduated. Over the years, that number slowly grew. While the School’s commitment to diversity and embracing the gifts of all children was constant, that commitment varied from Board member to Board member, from teacher to teacher, and from parent to parent. It could, of course, have been no other way. For many students, even the limited diversity of the School was a great blessing to them, introducing them to students and teachers of different backgrounds that they would not have met otherwise. Some students only realized this when they left the School. WFS student Alisa Elkis remembered learning about issues of racial discrimination only after her parents decided that she would attend the local public school in Woodbury instead of making the transition to Mullica Hill. Many years later, parent (and future teacher), Chris Mahon and her husband Jack decided to send their daughter Bridget (and later son Brandon) to Friends School Mullica Hill. “When we lived in Elmer,” remembered Chris, “there were no Black people”, but when we enrolled Bridget in 4th grade “lo and behold, she had a Black teacher, which was wonderful. And there were Black kids in her class, and she hadn’t encountered any Black people… and we were really glad that we sent them.” Ironically, the African American teacher that Chris Mahon admired so much was Karen Washington, one of Alisa Elkis’s great friends from Woodbury and now a teacher at Mullica Hill. Not all parents reacted, as did the Mahons. Kimberly Camp remembered that she and some of her fellow students of color were called into the Head of School’s Office “because some of the parents were upset that their children were emulating the African American students. They wanted to wear Apple caps, which the Jackson Five used to wear. They wanted to wear Black power t-shirts. They wanted to listen to the music we listened to and the parents were upset.” Kimberly and her fellow students were “asked to go before the entire student body and explain ourselves and to give people a lesson in who we were and what we were doing.” Kimberly remembered that the students did it, but that putting the onus on the African American students was less than ideal. As Kimberly aptly noted it was “something that the school can always aspire to do better. It’s something our society has to do better.” Regardless, Kimberly noted “that students that came through that experience seem to have healthier attitudes afterwards… you go into a situation where you try to help people be better people, to understand things from a different perspective, to try to get people to open up, challenge their assumptions, consider something else. That was a part of the education that I hope always sticks. For some it has, for others it hasn’t.” Neither the appointment of Beth Reaves nor the Garvin Prize demonstrated that the School had perfected how to best lift up each and every child, no matter their background, but these 2 moments were important and welcome signs that the struggle continued as the School approached its 50th anniversary.

Follow and Contact Us